Twenty Thousand Leagues, written in 1870, is arguably one of the greatest classic Science Fiction books written by a man whom many consider to have created the genre of science fiction writing.

A scientist and his servant are rescued at sea by Captain Nemo, a brilliant engineer and captain of the giant submersible ship, the Nautilus. They are held captive onboard the vessel and go with Nemo as he travels the entire world, exploring the seven seas: from volcanic islands to wrecks and ruins, from under water caves to the Antarctic ice shelves and encountering all manner of sea life along the way; both beautiful and hostile. But Nemo holds many secrets, and as the men become resigned to their life at sea they begin to suspect their course has a sinister element.

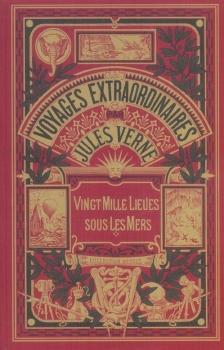

The copy of the novel reviewed here is a Hardback edition with a gilt cover showing a submarine and purports to contain the complete text of Verne’s original masterpiece. It was translated into English by Philip Schuyler Allen in 1922 and has since been reprinted by Reader’s Digest. This translation is considered by some to be one of the best English translations out there.

1. Biography and Translation

To appreciate the genius that is Twenty Thousand Leagues, we must first understand Jules Verne himself, the history of the book, and the socio-political environment that he was writing in. Jules Verne (1828-1905) was a French author whom, despite his amazing array of adventure stories, is purported to have never left France. This however is inaccurate as, between 1859 and 1887 he traveled between the UK, Scandinavia, Europe and North America.

Twenty Thousand Leagues was just one entry into a series called “The Extraordinary Voyages.” This was to be a most ambitious project that, throughout his career, dominated his works. His aim was to write about the sky, earth, ocean, space, forests, cities and peoples of the world, and to lead the Victorian readers through a journey of ‘the history of the universe’

In 1873 Mercier Lewis translated Vingt mille lieues sous les mers: Tour du monde sous-marin (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas: An Underwater Tour of the World) into English for the first time. With this translation nearly a quarter of the original text was cut out, and numerous translation errors were made.

Whatever the reasons for the mistranslations, this became the standard English version for over a century. This version also served for a while as ‘the definitive’ copy, and was used time and time again for adaptations and further translations, spreading the mistakes and diluting the original text rapidly.

Twenty Thousand Leagues has been re-translated time and time again, each time it has improved in some areas whilst suffered in others. Many of the inaccuracies and weak plot-elements previously attributed to Verne have been identified as mistranslations or poor editing by publishers. Unfortunately, these mistakes have often seen Verne’s work labeled as ‘children’s fiction’ and it has often been under appreciated or over looked. It is suggested that if the reader understands French then they should read the original French text, as it offers a more compelling and complex adventure than even the best English copy today.

In 1863 the Polish rose up against the Russian Empire. Nemo was originally to have been a Polish refugee seeking revenge against the Russian Czar who had massacred his family. This character background would have made for a drastically different Nemo, and thus a much darker and more pessimistic adventure. Sales of Verne’s works were very high in Russia, and the editor strongly opposed the character, fearing a sales backlash. After some discussion a compromise was made, and Verne created the character of Nemo as the famous trope that he now is – an enigmatic nobody with a mysterious yet tragic past (Nemo is literally latin for No One.)

2. The Science of Twenty Thousand Leagues

The greatest accomplishment of this book is the sheer scientific accuracy. Verne was one of those historical figures who had an amazing and uncanny ability to accurately predict technological and societal changes (The greatest example being his long-forgotten book Paris in The Twentieth Century – rediscovered a hundred years after it was written.)

The Nautilus is no coal and steam operated ship: It is a giant, iron-clad submersible powered by electricity. The electricity is generated from sodium/magnesium batteries which extract sodium from the ocean itself, and this in turn powers the motors, electric lights and life-support systems; the brilliant Nemo also has weapons that fire “electric bullets” to kill or stun sea-life as necessary.

Among many other ideas included are air-locks, SCUBA equipment, halogen lights, synthetic rubber and wetsuits, electromagnetic coils in the submarine motors, a salt-water distillation plant and even advanced manouvering techniques such as hydroplaning and motorized ballast pumps. The genius of these ideas was in the fact that electricity was still a novel discovery – Michael Faraday only having created the electric dynamo in 1837, and Tesla not fathering the birth of commercial electricity until the end of the 19th Century – and that the oceans had not yet been explored.

Jacques Cousteau was inspired by Twenty Thousand Leagues and even helped refine modern diving apparatus into what became known as SCUBA gear in the 1940’s – about sixty years after Verne described it, and Neoprene (synthetic rubber) wetsuits not being invented until the early 1950’s. In the 1880’s submarines were beginning to be built and the diving systems were functionally identical to those described by Verne. It wasn’t long before the Spanish Navy built the worlds first electric submarine in 1887. The Piezar – a device only recently patented in 2005, and as you read this, currently being implemented into American and European police and military arms, is a non-lethal stun gun that fires an electrically charged shell from a gun that also acts just as Verne imagined.

3. Substance and Style

Let’s start with labels – everyone loves labels. Modern readers typically classify Verne’s work as Steampunk – Victorian science fiction where fictional technology was limited by the existing steam-based technology at the time, and where there is a strong Colonial or Victorian aesthetic. I would argue that, to further sub-label Twenty Thousand Leagues, that it would be classified in the two genres of Hard Science (fiction dominated by technically accurate descriptions and calculations and often full of scientific jargon,) and Teslapunk (a relatively obscure offshoot from Steampunk, where technology is dominated and limited by electricity instead of steam but retains the Victorian aesthetic.)

Labels did not apply in Verne’s day. There were simple genres, and this was a Science Fiction Adventure book. No more, no less. The science does not distract from the story, rather it drives and enhances it. Readers in the late 1800’s expected to learn as well as be educated, and this book does that well through fantastic descriptions of the undersea landscapes, lifeforms, sea-life behavior, and even man’s place in the world.

The book takes you to almost every conceivable ocean environment, including some that are purely fiction. The world was still largely unexplored, and the oceans were a mystery, so it is a marvel that the book is still relevant nearly a hundred and fifty years after being written, and with a few exceptions (Sperm whale behaviour, shark hunting behaviours, and the geography and fauna of the South Pole) still remains accurate. The aforementioned inaccuracies are forgivable, as animal behaviours had not properly being studied yet – most of what we know attributed to Cousteau or Attenborough – and the South Pole was not to be reached until Roald Amundsen’s expedition in 1914.

The main characters are a French scientist, his servant, and a crewman from their ship. Initially they are part of a campaign to track down a giant narwhal thought to be attacking ships. Their ship is attacked, they are cast overboard, and are eventually grudgingly rescued by The Nautilus and her crew. The three men are forbidden from leaving the Nautilus and are carried around the world in literature’s greatest undersea milieu story ever.

Professor Pierre Aronnax and his associates Conseil and Ned Land, are our protagonists. Aronnax takes centre stage while the others play supporting roles. Nemo plays a complex character who walks the line between hero, anti-hero and villain – some see him as the main villain of the story, but truthfully the only real antagonist here is the ocean and nature herself. This book was written in a time when man and his inventions were setting out into the world to conquer the land and seas. The chaotic and anarchic qualities of nature made her the perfect foe for a world entering it’s great industrial revolution, where man now functioned on logic and mathematics, and anything that inhibited technological development or discovery was a foe to mankind and to science itself.

The characters are all likable, and though Verne struggles with the humorous scenes, they are few in number and help to develop the characters in ways that prove important to the plot later in the book. Often Victorian writers suffer from flowery language – Verne, however, avoids this pitfall though he does have a tendency to resort to ‘grocery-lists’ when naming species of fish present. In general the prose is fantastic and this version is well translated and a fantastic read. The opening line immediately grabs your attention and holds you until the books end.

The year of grace 1866 was made memorable by a marvelous event which doubtless still lingers in men’s minds. No explanation for this strange occurrence was found, and it soon came to be generally regarded as inexplicable.

When reading this book it is important to think of it in terms of a Victorian audience – all concepts in this book were foreign or radical, and it was an astonishing read to a world yet still dependent on wooden ships powered by coal and steam. Twenty Thousand Leagues leaves the reader, today, just as astounded by the book as it did to readers in 1870, and for the same reasons. The settings and characters are amazing, but the science is absolutely astounding. Twenty Thousand Leagues is timeless – just as in the 1870’s, readers now are still astounded by the science. But rather than be amazed at how far ahead of us it is, we marvel now at how far ahead it was in it’s time – we marvel that Verne could imagine technologies and social constructs, some of which are still now only being developed and refined. And as ever, just like space travel, we will always marvel at the alien underwater world Nemo lives in – because it is one the majority of us shall never explore in our lifetimes and we must rely on works like Verne’s to take us there.

There were several parts of the book which pull you out of the narrative and into the real world due to their shocking nature. For example, the crewman often wear clothes made from fur seal skins, and among the many ocean delights they feast upon, there is one instance where our main characters feast upon roast tortoise and sautéed dolphin livers. Conservationism, though a subject explored briefly and lightly in this book, was still a long way from being a strong movement.

A brilliant read, and a stoic classic that will keep astounding many more generations of readers. Recommended to anyone that loves Steampunk, Adventure Stories, Science Fiction, or Travel Stories.

Sources/Credits

- Jules Verne – Wikipedia.

- After Word – Clifton Fadiman (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea) ISBN 0-89577-347-3

- The North American Jules Verne Society, Inc

- 8 Jules Verne Inventions That Came True – National Geographic

- Nautilus – Wikipedia

Please share or reblog this review if you enjoyed it.

An amazing hard science fiction novel which became the father and tropenamer of steampunk even though, as you say, it isn’t a steam powered vessel.

LikeLike

I Love This Story I Read This Book 100’s of times

LikeLike

I am a fan of a juiels vern’s book

LikeLike